In driesd 's collection

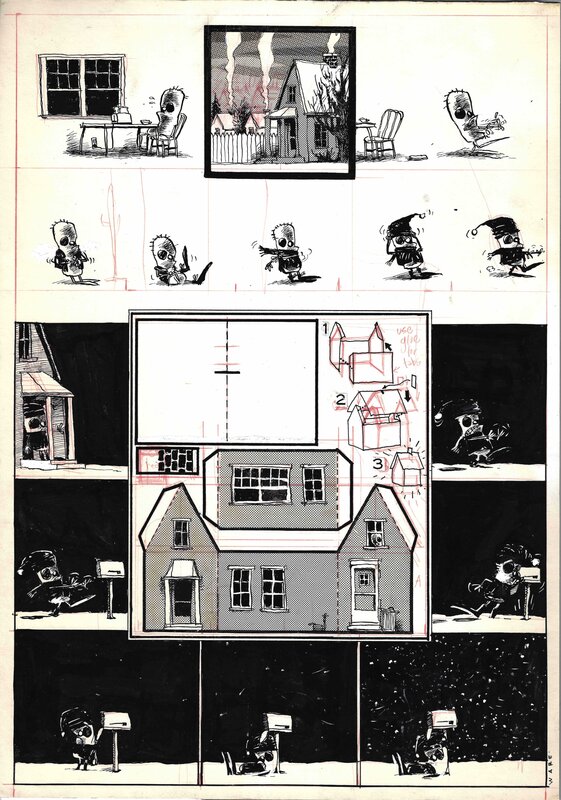

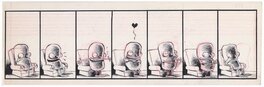

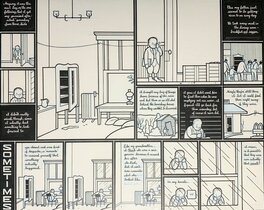

Chris Ware - Waking Up Blind, Cut out house

Mixed Media

Ink, colored pencil and white gouache on board

29.5 x 41.9 cm (11.61 x 16.5 in.)

Added on 2/1/18

Link copied to clipboard!

Comment

Early Chris Ware (1988). During that time Chris Ware studied at the University of Texas in Austin and regularly contributed to the "Daily Texan".

In Monograph Chris Ware comments:

"By the autumn of 1988 a long-term relationship (my first) with a lovely, kind girl had come to an end and the overall emotional effect of it was like having a hole punched through my ribcage; no matter what I did or where I was I couldn't stop thinking about the girl whom I'd been in love but now for a host of reasons companionship was no longer tenable. On the upside, I realized during those grey fall months that in any real relationship there aren't just two people, but a third, indefinable presence and feeling that the two unknowingly create together - and which in ending the relationship they both must suffocate in order to survive.

For no good reason, drawing the blinded potato character was the only thing that made me feel better. Having abandoned the use of words a few months earlier because I realized I was relying on them too much - the old "telling versus showing" problem of any young artist - I was also forced to focus on the internal rhythms of what are sometimes called "silent" comics. But the label of "silent" already admits something odd going on: when one reads words one is still "hearing" something in one's mind, however imaginary. even stranger, I noticed that I was still hearing something even when I read only pictures - and, more importantly, that I was relying on this imaginary sound to write the stories, much along the lines of how a composer might work (i.e., by playing or reading, it over and over again until it "sounded right.") Somehow, it became clear to me that underneath the balloons and in between the panels something akin to the music of emotional gestures that fills our days was being recreated, and if I wanted to really try to discover, and especially to harness, the unique power of what comics could be beyond flat illustrative pictures with words simply stuck on top of them, I had to listen to it. It's the method I still use when writing, though I long ago put words back into the mix.

Recent scientific studies suggest that as babies our senses overlap each other in ways that are unpredictable and blurred, and it seems to me there's perhaps something synthæsthetic preserved from this early mode of consciousness within the medium of comics itself. Given that children try to find a way to reproduce sound and sensation in their drawings (until they learn "not to") and that comics were, until recently, considered a children's literature, I don't think it's a stretch to make such a connection, though the stereotype of comics as a children's art developed from a somewhat separate set of cultural biases.

It was the comics of George Herriman, especially those he drew without his characteristicly poetic libretti, that really made it clear to me it was possible to have a cartoon character come alive, if not even live, on the printed page. Something about the received ideas of the theatrical

proscenium arch paired with his not treating the comic panel as a camera lens - as did the generations which followed him - allowed his figures to move about and live on paper unlike any other. Flickers of this ballet-like approach can be found in the work of A. B. Frost, Caran d'Ache and H. M. Bateman, but it was Herriman who really made it work. This is one of the aims of art - to make something that isn't just a picture of life but has a life of its own. It was with the rise of motion pictures in the 1930s that comics, right when it was realizing itself as its own form, adopted the language of cinema and all but shut down this approach, forfeiting its power as a drawn art until the advent of the Underground comics of the 1960s."

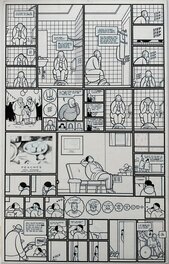

Chris Ware's first publication for a larger audience was a "Waking Up Blind" story for Raw 2. Vol 2. "Required Reading for the Post-Literate", from 1990, edited by Art Spiegelman and Francoise Mouly. (not this page...).

For a little backstory of how the young Chris Ware came under the attention of Art Spiegelman:

- Excerpt from an article in The Economist:

https://www.economist.com/1843/2013/08/27/chris-ware-everyday-genius

"In 1987, the Daily Texan interviewed Art Spiegelman and sent him a copy of their article. On the back was a fragment of a comic strip. "It was already a re-invention of what comics are," Spiegelman says over coffee at his loft in Lower Manhattan. "There was no signature, as I remember, so I got back in touch with them and asked if they could send me more of this person’s stuff. So they did. Then I had to find him."

When Spiegelman phoned, Ware thought it was a prank call. When he realised it wasn’t, he was terrified. Since discovering Raw back in Omaha, he had often had a copy of the magazine open on his desk while he worked. At 17 he’d begun a "Maus"-like comic of his own. "He said that it was his life's dream to publish in Raw but that he wasn’t ready," Spiegelman says, "that he was just a kid."

For three years Spiegelman tried to persuade Ware to send work to publish. Sometimes he would send comics to show what he was up to. "He had to be coaxed," Spiegelman says. "A letter would arrive which was five times the number of pages as the piece he was making but it would be specifically to say he’s inept and can’t do it. He had to be talked down and talked back into it." Eventually he capitulated, and published strips in the magazine in 1990 and 1991."

- In this video Art Spiegelman talks about this:

https://vimeo.com/143064558

- https://www.nybooks.com/online/2018/01/03/being-chris-ware/?lp_txn_id=1554294

His first success for the college newspaper, The Daily Texan, was a loosely drawn potato-shaped creature, inspired, as he says, by “George Herriman, Robert Crumb, Kaz and Charles Burns.” At a certain point, Ware altered the potato’s face by jabbing out its eyes, and the comic strip thus came to be called “Waking Up Blind.”

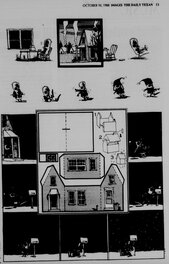

First published in the Daily Texan on the 10th of October 1988 (see additional image).

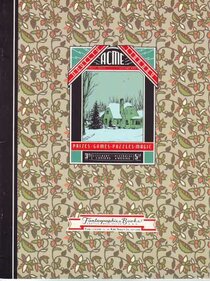

Published in Acme 3 and Monograph. In Monograph you can see a nice full page reproduction of this original art.

Bought at the Adam Baumgold Chris Ware expo in 2017.

Exhibited in Antwerps at Grafixx (2023).

In Monograph Chris Ware comments:

"By the autumn of 1988 a long-term relationship (my first) with a lovely, kind girl had come to an end and the overall emotional effect of it was like having a hole punched through my ribcage; no matter what I did or where I was I couldn't stop thinking about the girl whom I'd been in love but now for a host of reasons companionship was no longer tenable. On the upside, I realized during those grey fall months that in any real relationship there aren't just two people, but a third, indefinable presence and feeling that the two unknowingly create together - and which in ending the relationship they both must suffocate in order to survive.

For no good reason, drawing the blinded potato character was the only thing that made me feel better. Having abandoned the use of words a few months earlier because I realized I was relying on them too much - the old "telling versus showing" problem of any young artist - I was also forced to focus on the internal rhythms of what are sometimes called "silent" comics. But the label of "silent" already admits something odd going on: when one reads words one is still "hearing" something in one's mind, however imaginary. even stranger, I noticed that I was still hearing something even when I read only pictures - and, more importantly, that I was relying on this imaginary sound to write the stories, much along the lines of how a composer might work (i.e., by playing or reading, it over and over again until it "sounded right.") Somehow, it became clear to me that underneath the balloons and in between the panels something akin to the music of emotional gestures that fills our days was being recreated, and if I wanted to really try to discover, and especially to harness, the unique power of what comics could be beyond flat illustrative pictures with words simply stuck on top of them, I had to listen to it. It's the method I still use when writing, though I long ago put words back into the mix.

Recent scientific studies suggest that as babies our senses overlap each other in ways that are unpredictable and blurred, and it seems to me there's perhaps something synthæsthetic preserved from this early mode of consciousness within the medium of comics itself. Given that children try to find a way to reproduce sound and sensation in their drawings (until they learn "not to") and that comics were, until recently, considered a children's literature, I don't think it's a stretch to make such a connection, though the stereotype of comics as a children's art developed from a somewhat separate set of cultural biases.

It was the comics of George Herriman, especially those he drew without his characteristicly poetic libretti, that really made it clear to me it was possible to have a cartoon character come alive, if not even live, on the printed page. Something about the received ideas of the theatrical

proscenium arch paired with his not treating the comic panel as a camera lens - as did the generations which followed him - allowed his figures to move about and live on paper unlike any other. Flickers of this ballet-like approach can be found in the work of A. B. Frost, Caran d'Ache and H. M. Bateman, but it was Herriman who really made it work. This is one of the aims of art - to make something that isn't just a picture of life but has a life of its own. It was with the rise of motion pictures in the 1930s that comics, right when it was realizing itself as its own form, adopted the language of cinema and all but shut down this approach, forfeiting its power as a drawn art until the advent of the Underground comics of the 1960s."

Chris Ware's first publication for a larger audience was a "Waking Up Blind" story for Raw 2. Vol 2. "Required Reading for the Post-Literate", from 1990, edited by Art Spiegelman and Francoise Mouly. (not this page...).

For a little backstory of how the young Chris Ware came under the attention of Art Spiegelman:

- Excerpt from an article in The Economist:

https://www.economist.com/1843/2013/08/27/chris-ware-everyday-genius

"In 1987, the Daily Texan interviewed Art Spiegelman and sent him a copy of their article. On the back was a fragment of a comic strip. "It was already a re-invention of what comics are," Spiegelman says over coffee at his loft in Lower Manhattan. "There was no signature, as I remember, so I got back in touch with them and asked if they could send me more of this person’s stuff. So they did. Then I had to find him."

When Spiegelman phoned, Ware thought it was a prank call. When he realised it wasn’t, he was terrified. Since discovering Raw back in Omaha, he had often had a copy of the magazine open on his desk while he worked. At 17 he’d begun a "Maus"-like comic of his own. "He said that it was his life's dream to publish in Raw but that he wasn’t ready," Spiegelman says, "that he was just a kid."

For three years Spiegelman tried to persuade Ware to send work to publish. Sometimes he would send comics to show what he was up to. "He had to be coaxed," Spiegelman says. "A letter would arrive which was five times the number of pages as the piece he was making but it would be specifically to say he’s inept and can’t do it. He had to be talked down and talked back into it." Eventually he capitulated, and published strips in the magazine in 1990 and 1991."

- In this video Art Spiegelman talks about this:

https://vimeo.com/143064558

- https://www.nybooks.com/online/2018/01/03/being-chris-ware/?lp_txn_id=1554294

His first success for the college newspaper, The Daily Texan, was a loosely drawn potato-shaped creature, inspired, as he says, by “George Herriman, Robert Crumb, Kaz and Charles Burns.” At a certain point, Ware altered the potato’s face by jabbing out its eyes, and the comic strip thus came to be called “Waking Up Blind.”

First published in the Daily Texan on the 10th of October 1988 (see additional image).

Published in Acme 3 and Monograph. In Monograph you can see a nice full page reproduction of this original art.

Bought at the Adam Baumgold Chris Ware expo in 2017.

Exhibited in Antwerps at Grafixx (2023).

9 comments

To leave a comment on that piece, please log in

About Chris Ware

Franklin Christenson Ware, known as Chris Ware, is an American comic book writer. Since 1993 he has published the Acme Novelty Library, a series with an irregular format and periodicity. Jimmy Corrigan, his main work (1995-2000), has won him numerous awards in the English-speaking world (several Ignatz, Harved and Eisner awards, as well as an American Book Award and the Guardian First Book Award) as well as in the French-speaking world ("Prix du meilleur album" at the Angoulême Festival and the Prix de la critique).